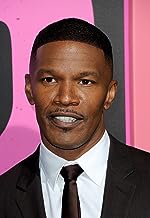

Jamie Foxx

Joe (voice)

Filmography:

- Collateral: Max

- Ray: Ray Charles

- Django Unchained: Django

- Dreamgirls: Curtis Taylor Jr.

In about 100 jaunty, poignant minutes, “Soul,” the new Pixar Animation feature, tackles some of the questions that many of us have been losing sleep over since childhood. Why do I exist? What’s the point of being alive? What comes after?

It’s rare for any movie, let alone an all-ages cartoon, to venture into such deep and potentially scary metaphysical territory, but this is hardly the first time that the studio has directed its visual and storytelling resources toward mighty philosophical themes. “Soul” follows “Coco” in conjuring a detailed vision of the afterlife — and also, in this case, the before-life — and joins “Inside Out” in turning abstract concepts into funny characters and vivid landscapes. The world that human souls pass through on our way into and out of life is a glowing, minimalist realm of embodied metaphors and galaxy-brain jokes, populated by blobby, ectoplasmic souls and squiggly bureaucratic “counselors” named Jerry.

But at the same time, “Soul,” directed by Pete Docter and Kemp Powers from a screenplay they wrote with Mike Jones, represents a new chapter in Pixar’s expansion of realism. (Slated to open in theaters earlier this year, it is streaming on Disney+.) Having conquered fish scales in “Finding Nemo,” beastly fur in “Monsters Inc.,” metal in “Cars” and vermin in “Ratatouille,” the animators have set themselves more subtle challenges.

Though other Pixar projects have visited actual places (Paris, San Francisco, the Great Barrier Reef), this is the first to dive fully into the multisensory moods of a living city, chasing after its rhythms, its folkways, its architectural details. “Soul” is a movie about death, about jazz, about longing and limitation. It’s also a New York movie.

As such, it traffics in a brusque urbanist sentimentality that isn’t immune to or afraid of cliché. The sensory riot of the city includes squalling car horns, clattering trains, bagels, slices of pizza, barbershops, subway platforms and the perpetual-motion bustle of pedestrians, strollers, yellow cabs and more. Everything we used to complain about and miss desperately now.

All of this is rendered — “drawn” isn’t the right word; some combination of “sculpted” and “orchestrated” is what’s needed — with graceful, kinetic precision. Like other great New York movies, it invites you to identify particular intersections and storefronts, to compare its imagined geography with the city of your own experience.

It isn’t all noise and crowds. Part of the Pixar aesthetic over the years has been to collapse the distance between animation and other kinds of cinema, and you would swear that the New York scenes in “Soul” were filmed in natural light. There is a beauty that is almost spiritual in the way the sun falls across a block of rowhouses, through the windows of a storefront or along the floorboards of a walk-up apartment. Or maybe not “almost.” The apartment belongs to a pianist named Joe Gardner (voiced by Jamie Foxx), whose literal struggle to keep body and soul together drives the plot across the city and into the beyond.

Joe, a jazzman like his late father, is at a crossroads. No longer young — though we don’t know exactly how old — he makes a living teaching music to middle-schoolers while chasing after gigs. His mother (Phylicia Rashad) worries about his prospects. A full-time job offer and a chance to sit in with a band led by an A-list saxophonist (Angela Bassett) arrive on the same day, which also turns out to be the last day of Joe’s life.

Sort of. The sheer inventiveness of “Soul” makes it impossible to spoil, but because it’s dedicated to surprise, to the improvisational qualities of existence, I want to tread lightly. Suffice it to say that Joe finds himself suddenly transported from Manhattan to a limbo where he meets a rebellious soul known as 22, who speaks in the voice of Tina Fey.

Not yet assigned to a definite human form, 22 has chosen that voice for its annoying qualities, and she has spent much of eternity driving everyone crazy — except for the Jerrys, who possess infinite patience (and speak in the soothing tones of Wes Studi, Alice Braga and Richard Ayoade). There’s also someone called Terry (Rachel House), the resident bean counter, who is a pricklier character, and as much of a villain as this gentle, melancholy fantasy needs.

Anyway, 22 doesn’t see the point of going down to Earth to take up residence in a body. Joe is desperate to get back into his, and their conflicting, complementary desires send them back to Earth in a switched-identity caper. Each one is the other’s wacky sidekick, and each teaches the other some valuable lessons.

The didacticism of the movie is sincere, not unwelcome, and inseparable from its artistry. Jazz, far from being incidental to “Soul,” is integral to its argument about how beauty is created, sustained and appreciated — and to its grounding of a specifically Black experience in New York.

Joe’s playing is energetic and serene, and it carries him into a zone that is wittily literalized as an area between Earth and the spirit world. (Other visitors to this liminal region include a street-corner mystic named Moonwind, voiced by Graham Norton.) Jon Batiste’s lovely jazz compositions take turns with Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s subtle, cerebral score, building a sonic bridge between the sensual and the abstract, the physical and the metaphysical.

Like other Pixar films, “Soul” is aware of its own paradoxes. The “Toy Story” cycle is a humanist epic about inanimate objects. “Inside Out” is an exuberant fable about the importance of sadness. This is a mightily ambitious warning against taking ambition too seriously. Every soul, the Jerrys explain, has a spark that sends it into the world. Joe and 22 take this to mean that everyone has a unique purpose, a mistake that reflects a competitive, careerist ideology that the movie can’t entirely disown.

But it is nonetheless open to other possibilities, which may be all that any work of art can be. “Soul” tries, within the imperatives of branded commercial entertainment, to carve out an identity for itself as something other than a blockbuster or a technologically revolutionary masterpiece. It’s a small, delicate movie that doesn’t hit every note perfectly, but its combination of skill, feeling and inspiration is summed up in the title.

Pixar's "Soul" is about a jazz pianist who has a near-death experience and gets stuck in the afterlife, contemplating his choices and regretting the existence that he mostly took for granted. Pixar veteran Pete Docter is the credited co-director, alongside playwright and screenwriter Kemp Powers, who wrote Regina King's outstanding "One Night in Miami." Despite its weighty themes, the project has a light touch. A musician might liken "Soul" to an extended riff, or a five-finger exercise, which is very much in the spirit of jazz, an improvisation-centered art that's honorably and accurately depicted onscreen whenever Joe or another musician character starts to perform.

Where do people get their personalities? Do parents play a part, or are such things somehow determined before birth? For centuries, doctors of psychology, doctors of philosophy and doctors of theology have contributed their thoughts on the subject, but the latest breakthrough comes from another kind of doctor entirely: Pete Docter, the big-idea Pixar brain behind outside-the-box toons “Inside Out” and “Up,” who takes a look deep inside and comes up with another intuitive, easy-to-embrace metaphor for — dare I say it — the meaning of life.

This typically ambitious Pixar animation comes on like a fever-dream cross between Disney’s Fantasia and Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death, with a bizarre hint of Peter Jackson’s The Lovely Bones thrown in for good measure. A tale of a music teacher who loses his life but discovers his soul, it’s a visually sumptuous riot of ideas, pitched somewhere between a playful musical, a divine comedy and a metaphysical drama.

What is “soul”? ? Is it that feeling you get when you tap into the flow between emotion and expression, the spiritual and the physical? Is it something personal percolating within you, waiting to be unleashed? Is it the essence of humanity in a nutshell? Defining the concept is like aiming at a constantly skittering target. You sense it when you sense it. I know you’ve got soul.

Pixar has made movies that have ventured into the afterlife, opened on the blighted remnants of a postapocalyptic Earth, and regarded the immensity of death through the eyes of a set of beloved anthropomorphic toys. But with Soul, which hits Disney+ on Christmas Day, the animation giant takes on what has to be its most unlikely subject matter yet for what’s technically a children’s film: the dilemma of whether to keep chasing gig-economy dreams or to take an uninspiring staff job that comes with some very handy health benefits. Admittedly, the character facing this decision — a jazz pianist named Joe Gardner (voiced by Jamie Foxx) who’s been working as a part-time band teacher while waiting on a music career that never seems to materialize — does spend a good stretch of the runtime as a talking cat. Still, if Pixar has, in recent years, fallen into a rhythm of alternating unpredictable originals with safer sequels to the proven hits, Soul plays not just like one of the former, but like the accumulation of a decade’s worth of odd ideas. It’s whimsical and bold and also easier to admire in the abstract than to get deeply emotionally invested in, though it features a late-breaking burst of beauty that will soften the hardest of hearts.

Joe Gardner is a middle-school band teacher who gets the chance of a lifetime to play at the best jazz club in town. But one small misstep takes him from the streets of New York City to The Great Before – a fantastical place where new souls get their personalities, quirks and interests before they go to Earth. Determined to return to his life, Joe teams up with a precocious soul, 22, who has never understood the appeal of the human experience. As Joe desperately tries to show 22 what’s great about living, he may just discover the answers to some of life’s most important questions.